Forging Firsts: Gloria Ladson-Billings

Beyond the Lesson Plan: How a Series of Questions Sparked My Belief

11/26/2024

"Forging Firsts" is a series that shares the stories of individuals who have accomplished remarkable achievements in their journeys. Each story, talks about when they became the “first” whether that is breaking records, facing challenges, or creating new paths. The series explores how these experiences helped them grow personally, uncovering new strengths and depths within themselves. "Forging Firsts" highlights the meaningful impact they have and how they’re inspiring others to follow in their footsteps.

My story begins in Philadelphia, PA, where I was born to parents who entered the working world at a very young age. Although they didn’t have access to education, they instilled in me core values like respect and the courage to speak up when something felt wrong.

The first person to broaden my view of what was possible was my fifth-grade teacher, Ms. Ethel Benn - a remarkable Black woman who saw potential in me and opened my mind to all that I could be.

One day, she turned to me and asked, “What makes you think you can’t be the smartest fifth grader in this classroom?” Her words caught me by surprise.

She continued, “Why not the smartest in the school? The city? The state? The world? Someone must be, so why not you?” Her belief in me was revolutionary, and her words have stayed with me ever since.

While my parents emphasized good behavior and respect, Ms. Benn taught me the power of learning and knowledge. She introduced us to Black history, even though it wasn’t part of the official curriculum. I remember taking turns keeping an eye out for the principal as she brought to life stories of W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Ms. Benn sparked my love for history and English, a passion I still maintain to this day.

As I grew older, I became keenly aware of disparity. I noticed that other students had resources and connections I lacked. They typed notes on their own typewriters, and their parents’ jobs opened doors and opportunities that were out of reach for my family. I’ll never forget a science project that I was unable to complete, not because I didn’t want to or wasn’t capable, but because I didn’t have the materials needed to do it. It wasn’t that other students were smarter than me, they just had different resources. I began to realize that the playing field wasn’t level, and the difference wasn’t in intelligence but in opportunity.

I observed and experienced these disparities throughout high school, which led me to a pressing question: How many kids aren’t succeeding simply because of their environment, and what can we do to provide the resources they need to thrive? Asking these critical questions shaped my philosophy on education and sparked my desire to create opportunities for others.

For Black students at my high school, the way out seemed to be through athletics – that’s the path legends like Wilt Chamberlain took. But I was determined to pursue a different route, one where I allowed my mind to lead me to a fulfilling life.

In college, just as in high school, I excelled in my history and English courses. But even with my love for learning, when the idea of becoming a teacher was suggested, I couldn’t quite see that as a path for me. Nevertheless, I needed to make a living, so I graduated with a degree in education, and returned to Philadelphia to teach at a local high school.

It wasn’t until I stepped into the classroom that I fell in love with teaching. The most rewarding moments were watching concepts come alive in my students’ minds, watching their excitement as they grasped new ideas rekindled my own love of learning.

The kids were great, but initially I faced a lot of intolerance from some of the parents. The school was located in a predominantly white, working-class community, and I was one of only three Black teachers there. I often was called a number of hurtful things, including the n-word.

I remember one student’s father passing away. I brought a condolence card signed by the class to the family’s home, not realizing that the wake was taking place at that very moment. Unfamiliar with the tradition of an in-house wake, I felt out of place and aware that I was surrounded by people who might not think kindly of me. Still, I stayed for the entire observance, drawing on my parents’ teachings about respect and compassion for others.

In the end, this act of empathy helped shift perceptions and earned me respect within the community. It was one of the first moments I truly understood how powerful shared experiences could be in bridging divides.

Why not the smartest in the school? The city? The state? The world? Someone must be, so why not you?Ms. Ethel Benn

I decided to transition into higher education, securing a fellowship with the University of Washington to earn my Master’s degree. After fifteen months, I met with my advisor, who encouraged me to stay for a PhD., but I felt I had accomplished all I set out to do, so I declined. He insisted, “you’ll be back to get your PhD., even if it’s not here in Washington.

True to his prediction, I eventually pursued my PhD. at Stanford. Initially, I didn’t expect that Stanford was made for me, but moving to California allowed me to teach and complete my studies in a place that was also ideal for my growing family, my three sons and later a daughter.

With my background as a former high school track athlete and my husband’s experience as an NFL player, it was no surprise that our kids developed a love for athletics. But we had one rule: each child had to participate in both a sport and an art each season or school year. This ensured they were well rounded and developed skills beyond their “playing field”. It also kept them out of trouble.

After five years at Stanford, and a beginning career at Santa Clara University, I was invited to give a talk at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I accepted the invitation, though I joked that I wouldn’t overstay my welcome for fear of the harsh Wisconsin winters. During my visit, I had a conversation with then Chancellor, Donna Shalala. I’ll never forget at one point during the conversation, she looked a t me and asked, “what do we need to get you here?”. I replied, “I already have a job.” Without missing a beat, she responded, “that’s not what I asked you.”

I eventually decided to give Wisconsin a try. It turned out to be one of the best decisions of my life.

Intellectually, Wisconsin was the perfect environment to push me and help me grow. It provided me everything I had hoped for and things I had never even thought of. Wisconsin empowers educators to innovate in ways that other schools would never consider.

How many kids aren’t succeeding simply because of their environment, and what can we do to provide the resources they need to thrive.Gloria Ladson-Billings

During my time here, I had the privilege of serving on the athletic board, the graduate research committee, and serve as a Big Ten Faculty representative. One of my responsibilities was approving athletic schedules, ensuring that travel demands didn’t overwhelm our student-athletes. I remember an early conversation with former basketball head coach Bo Ryan. I pointed out that his team’s proposed schedule had heavy travel and suggested giving the players a bit more rest. This allowed me to blend my love for education and sports.

I’ll never forget Anthony Davis, a former star running back, who came to me one day and shared his dream of becoming a teacher. Together, we worked out a schedule that allowed him to balance his classes, practices, and student-teaching hours. After a stint in the NFL, he returned to Wisconsin, earned his master’s degree, and eventually went to the University of North Carolina-Charlotte where he completed his PhD. Today, he’s the Dean of Students at Georgia State University. It’s experiences like these that truly capture the impact of a place that values education and opportunities, allowing students to pursue all of their dreams.

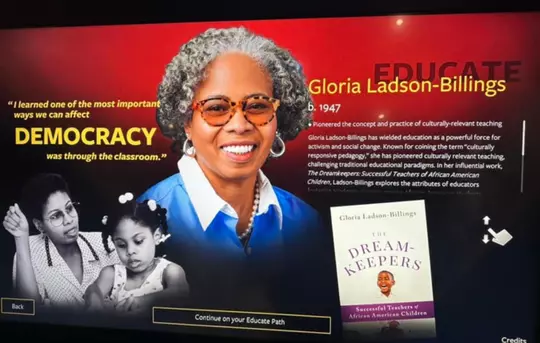

In 1995, I became the first Black woman to be tenured in the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. While it was an honor, there’s a bit of sadness that comes with it. The University has existed since 1848, and it took over a century for someone like me to reach this milestone. Still, I feel a deep sense of accomplishment when I see the Black women who have followed in my footsteps.

Over the years, I’ve supervised 55 graduate students, 19 of them Black women. If there’s one thing that I impart to them, it’s the importance of legacy. I remind them that their journeys are about more than just personal success – they’re also paving the way for others who aren’t here yet. They may face obstacles, but I’m here to support them and encourage them to keep moving forward, knowing they’re part of something much bigger.

Among today’s students, I sometimes sense a lack of hope. My parents lived through Jim Crow, hitchhiked their way to Philadelphia, and yet they instilled in us an optimism about the future. My generation fought in the civil rights era, but in some ways, we’ve regressed. As parents, we didn’t always pass on that same sense of progress and possibility. To truly nurture young people, we need to do more than just parent them—they need mentors, coaches, teachers. They need guidance so they don’t feel pressured to make adult decisions before they’re ready.

The excitement of learning, of tapping into our potential, is something I hope to inspire in my students. There’s a transformative power in using our minds and discovering what makes us truly come alive.

I talk about legacy often with my students, and I think about my own as well. My hope is not to be remembered solely as the first Black woman to earn tenure in the School of Education, but as someone who cared deeply, whose life’s purpose was to teach and guide others. I want people to remember me as someone who believed in the potential of every student and helped them discover that same belief within themselves. Just as Ms. Benn once asked me, I now ask my students, “why not you?”.