2020 UW Athletic Hall of Fame: Aaron Gibson

June 15, 2020 | Football, General News, Mike Lucas

Wisconsin holds a special place in big heart for former Badger All-American and NFL pro

|

||

|

The 2020 class of the UW Athletic Hall of Fame has been selected and new members will be announced from June 15 - 26. Visit UWBadgers.com each day to celebrate each new member of this distinguished and historic class of Badgers!

BY MIKE LUCAS

UWBadgers.com Senior Writer

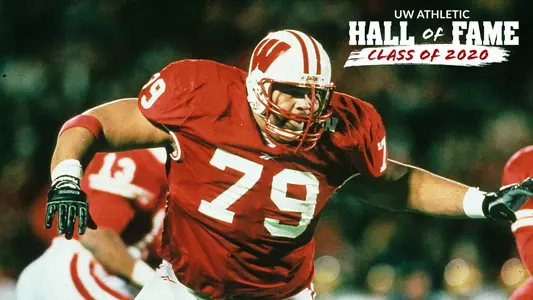

MADISON, Wis. — Aaron Gibson has a large Wisconsin flag hanging from the pole in the front yard of his home in Dallas, Texas. His man cave is mostly a shrine to the Badgers with framed photos and memorabilia from his playing career as a "Jumbo-sized" tight end and first-team All-American right tackle that blocked for tailback Ron Dayne.

Hanging from one wall is a picture of a picture.

The original was shot following the 1998 win over Penn State that clinched a berth in the Rose Bowl. Gibson, then a senior, is shown without his custom-fit helmet — the largest ever made by Riddell — biting down on a long-stemmed rose during the postgame celebration at Camp Randall Stadium.

Nearly two decades later, this memorable image of Gibson reappeared at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas, where the Badgers faced Western Michigan in the 2017 Cotton Bowl. Gibson and his wife Brigitte were in attendance and she snapped the photo of the photo, which showed up on the four video boards stretching between the 20-yard lines and towering 90 feet above the turf.

Gibby, supersized.

At one time, the two sideline-facing HD screens (160 feet wide by 72 feet tall) were the largest in the world. At one time, Gibson was a Cowboy and the largest player in National Football League history at 410 pounds. So much has transpired since that 2002 season in Dallas when Gibson was daily consuming upwards of 20,000-plus calories and admitted "I was literally eating myself out of football."

Today, his Cowboys helmet is in his man cave. Also featured in an NFL display case are his helmets from Detroit (where he was the Lions' first round pick, the 27th player taken overall, in the 1999 draft) and Chicago (where he briefly revived his career in 2003-04). He wore No. 78 with the Bears and the jersey is hanging on another wall alongside the No. 79 that he wore with the Badgers.

His Wisconsin degree holds a special place in the room and in his heart.

"Everything about the University of Wisconsin meant the world to me," said the 42-year-old Gibson, a communications major. "The degree was part of the whole experience that I will be forever grateful … education is powerful and as long as you always try and obtain as much knowledge as you can, there is never a ceiling on what you can achieve."

Soon there will be an addition to one of his walls. His UW Athletic Hall of Fame plaque. As a member of the 2020 class, Gibson will join previous inductees Joe Thomas, Chris McIntosh, Joe Panos, Dennis Lick and Paul Gruber among the Badgers' offensive tackles in the modern era wing.

When his former head coach Barry Alvarez, the current director of athletics, phoned Gibson and informed him of his induction, there was some dead air before Gibson innocently asked Alvarez, "Are you BS-ing me?" Assured this was no joke, Gibson said, "It blew my mind."

Upon deeper reflection, it was pretty overwhelming.

Overwhelming because there was nothing in his childhood foreshadowing a Hall of Fame.

"Say we take away all the hardships," he proposed of his narrative, "I just didn't have a thought that I would matter to anyone enough to think that I deserved this kind of an honor."

• • • •

During his freshman and sophomore years of high school — Decatur Central in Indianapolis — he grew from 240 to 320 pounds. Up until then, he was more committed to swimming and wrestling. As a concession to his growth spurt and peer pressure, he stuck with football.

Gibson struggled at first with the tempo and nuances of the game. But by the end of his junior year, he had settled into a comfort zone. As a senior, he was the team captain and a USA Today All-American. He played both ways. On defense, he recovered eight fumbles and broke up 11 passes.

UW assistant Kevin Cosgrove was the lead recruiter.

"You could tell the kid was an athlete," Cosgrove said at the time. "He had a good bounce in his step. He moved really well. Without even seeing film, I knew he had a chance to be a heck of a player. And once you watched film, it was pretty obvious. When you have a kid that size, word got out fast.

"As a senior, he was a dominating player. If they ran behind him, they were going to get yardage. But like most high school kids who dominate, his work ethic probably wasn't what it should have been. Still you could see when his number was called, there was a lot of effort."

Gibson did not live the life of most high school kids.

His family didn't have the financial wherewithal to establish roots in any one place.

To this day, he still remembers spending one year in a homeless shelter.

"I still think about it a lot," he said. "I was still being bussed to my same school and seeing the same kids that I saw when I wasn't living there (the shelter). But I was having to basically live a lie every day on where I was living. The bus would drop me off about a four-mile walk from the shelter.

"You had to be back at a certain time and there were times when I'd leave football practice early or I'd beg to get into the shelter because I was late. It was a place that I was thankful was there for me. But I always knew that it was a place that I never wanted to end up in.

"Because I didn't want to be in that situation, it gave me a work ethic that was different than just wanting to be a good football player or wanting to be a good student or wanting to be a good person. I just wanted to be better than having to go to that shelter and survive."

Gibson canceled scheduled recruiting trips to Ohio State and Penn State after visiting Wisconsin. The selling point was the family culture on the Madison campus. It was something he felt and viewed with his own eyes and said so upon committing, "I saw the players went out together as a team. Wherever you went, you saw the players together. It wasn't like that at the other schools."

As a freshman, though, he was basically isolated from the players as a Prop 48 casualty. Under those NCAA academic requirements for competition, he lost a year of eligibility. Plus, he couldn't practice with the team, a significant hardship because it led to detachment. He was often homesick. And Cosgrove spent a lot of time re-recruiting him to make sure he came back to campus after going home for weekends.

During that first year, Gibson came under the wing of Wisconsin's strength and conditioning coordinator John Dettmann, who was assisted by nutritionist Scott Hettenbach. They had their work cut out for them. When Gibson reported to school, he was carrying well over 400 pounds on his 6-foot-7 frame.

The first stage in Dettmann's weight loss plan was walking.

Dettmann and Gibson walked everywhere together.

It was how Gibson got to know his way around campus.

"Dett was the biggest influence on me, hands-down," Gibson said. "There was nobody who took a bigger interest in me or spent more time with me — in football or out, in class or out, in the weight room or out of the weight room. He said, 'I'm all for you if you give me everything you have.'"

Gibson started laughing, a signature high-pitched jovial laugh.

"He was one of those guys who would catch me doing anything I wasn't supposed to be doing," Gibson said of Dettmann's penchant for catching him eating fast food. "He must have had spies. I remember I was at McDonald's with another O-lineman and Carl McCullough came strolling in."

McCullough was a Parade All-America tailback out of Minnesota.

"We had to buy Carl his food," said Gibson, laughing louder, "so he wouldn't tell on us."

Gibson's breakthrough as a player came the following year in Columbus, Ohio.

On October 12, 1996, Barry Alvarez unveiled his secret weapon: a 373-pound tight end. During the bye week leading up to the Ohio State game, Alvarez came up with a couple of new formations. In one, Gibson either lined up to the right of tackle Jerry Wunsch or to the left of McIntosh, the left tackle.

Obviously, there was a surprise element to the Jumbo package and it was more effective in the first half than the second. But it opened the door for Gibson getting more playing time. His presence had Buckeyes defensive end Mike Vrabel quizzing Alvarez, "Where did that big guy come from?"

Gibson collapsed Vrabel on a running play and fell on him.

"I couldn't feel anything," Vrabel said later. "I'm thinking my career is over."

As it turned out, Gibson's was just beginning.

"Before my first start at tight end," Gibson said, "I thought I was big, I thought I was talented, I thought I could play. But when Barry put me in that Ohio State game and I was blocking those guys — Ohio State talented guys (like Vrabel, Matt Finkes and Luke Fickell) — I was handling them.

"And I'm thinking, 'Oh, my goodness, I can actually do this.'"

Gibson was still a curiosity because of his massive size (20.5-inch neck, 20-inch biceps, 40.5-inch sleeves, 47.5-inch waist, 33.5-inch thighs) and strength (745-pound squad, 475-pound bench). His agility was also freakish. He could dunk a basketball and do the full splits, touching his chest on the floor.

By early November, he was becoming more of a fixture as an extra blocker than a novelty. In the Purdue game, he helped open running lanes for Dayne, who rushed for 244 yards. Wearing jersey No. 81, per usual as a tight end, instead of his customary No. 79, Gibson made quite an impression.

"One of the officials told me on the sidelines that a Purdue player wanted to know if there was a weight limit for players in the 80s," Alvarez said, chuckling. "Gibby could flat-out block people. He caved in defensive lines. Running the zone and getting movement allowed Ronnie to do some things."

As a junior, Gibson took over as the starting right tackle, filling the void left by the graduation of Wunsch. In the 1997 Wisconsin football media guide, Gibson's bio appears on page 76 accompanying a photo with him in a tie and shirt. Meanwhile, all of his teammates are pictured wearing sport coats.

The school supplied jackets. But the stock went up to size 56. He wore a 62 coat.

Gibson got accustomed to drawing stares from strangers whenever he entered a room. Because of his broad shoulders, it was not unusual for him to enter sideways to get through the door frame. Iowa's All-America defensive tackle Jared DeVries aptly characterized Gibson, "Facing the guy is like trying to run around a mountain. Except the mountain moves."

Revisiting some of those memorable one-on-one confrontations between DeVries and Gibson, Alvarez said, "I remember Gibby hitting DeVries with an arm and it was like a bear swatting a cub. DeVries was actually rolling on the ground. That's how overpowering Gibby was."

On the field, there were opponents to overpower.

Off the field, there was adversity to overcome.

Especially after leaving Madison when he was more vulnerable than ever.

"Where I am today is only because of Wisconsin, and I don't just mean football," Gibson said. "Everything about me was shaped at Wisconsin. How I reacted to things. How I dealt with issues. How I talked things out with people. How I leveled all my emotions. It all came from Wisconsin.

"There have been so many things that have tried to kick me down the hill.

"The weight was trying to destroy."

After retiring from pro football, Gibson ballooned to 485 pounds. That was compounded by an addiction to painkillers; something that he traced back to his years in Detroit where he sustained a couple of serous shoulder injuries. "There was always something coming at me," he said.

Less than 10 years ago, he hit rock bottom. Living alone in his Dallas apartment, he was his own worst enemy. Until Brigitte walked into his world. Under her loving care and supervision, he changed his outlook on life and what he wanted out of it. He went from 485 to 290. Right now, he's at 310.

"I told her, 'You are the reason I am who I am, and I am where I am today,'" he said. "She has been my saving grace, my angel, my everything. She has always been there for me patiently saying, 'I see the potential in you, and we'll help get you where you need to be, and we'll be just fine.'

"She stuck with me. She helped me become clean. On February 1, I was four years clean. Not one painkiller even while having two amputations and having part of my hip removed."

That takes some explaining. About four years ago, Gibson was working in his backyard and got bitten by a poisonous brown recluse spider that is commonly found in Texas and southern regions.

Gibson didn't go immediately to the hospital. And when he did it was almost too late. "The doctor told me," he said, "if you would have stayed home 12 more hours you would have died."

His left toe was amputated. And because the infection had spread, some tissue from the left side of his hip was also removed. After returning home, he got sick again. The poison hadn't left his system, resulting in the loss of his left foot and three toes, including the big toe, on his right foot.

"People looking at me think I'm just walking like a guy who's sore rather than I'm literally counting every step," he said. "It's like walking on a stilt with my left leg. On the other side, it's like walking without your balance point so you have to put your foot down and think about every step.

"But I get around. I feel like I'm blessed because I can walk without a wheelchair.

"Me and my wife have our 17-year-old daughter still in the house.

"I sold my Dallas security company and I'm fully retired at 42.

"Life is really good right now."

Through all of the peaks and valleys, he has found a way to persevere and count those blessings.

The Alvarez phone call notifying him of his Hall of Fame selection sparked a flashback.

"I was on a stationary bike in the Wisconsin weight room and I was upset about something," Gibson said. "I remember one of my teammates walking up to me and saying, 'Listen, man, in this game, you're going to have some really high highs and you're going to have some really low lows.'

"If you keep riding those highs and lows, you're going to ruin yourself.

"So, you have to stay right here …"

The player held out a straightened right hand, palm down.

"That's how I've leveled my emotions in life," Gibson said.

2020 UW Athletic Hall of Fame

- Aaron Gibson, Football

- Carla MacLeod, Women's Hockey

- Ted Kellner, Special Service

- Jackie Zoch, Women's Rowing

- Mike Wilkinson, Men's Basketball

- John Byce, Men's Hockey and Baseball

- Tom Burke, Football

- Jessie Stomski, Women's Basketball

- Dick Bartman, Boxing

- Jeff Braun, Men's Track and Field

- Bo Ryan, Men's Basketball