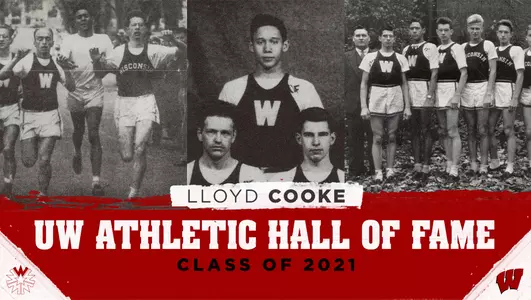

2021 UW Athletic Hall of Fame: Lloyd Cooke

June 17, 2021 | General News, Men's Cross Country, Men's Track & Field, Mike Lucas

Badgers’ first Black cross country student-athlete excelled as athlete and scientist

|

|

|

BY MIKE LUCAS

UWBadgers.com Senior Writer

In 1971, Marylin Bender, the first female Sunday Business editor at the Times, interviewed Cooke in his 34th floor office of the Union Carbide Building at 270 Park Avenue in midtown Manhattan.

Cooke, a planning manager and research scientist, had 30 years of technical and business planning experience and a host of professional and civic honors, the story pointed out.

Wrote Bender: "Lloyd Cooke's flair for problem-solving was manifested in his own career choice. Born and raised in the Midwest, he was advised by his father, a Federal Government engineer and architect, that his first love, aeronautical engineering, was a hopeless profession for a black.

"So he picked the slightly more enlightened field of chemistry. When he couldn't get a job after receiving his B.S. from the University of Wisconsin at the head of the class of 1937, he purposefully narrowed the field to basic research in cellulose chemistry.

"His first job as a research chemist in starch chemistry at the Corn Products Refining Company resulted from a paper he gave at a meeting of the American Chemical Society in 1941. He rose to a section group leader before being lured five years later to a research job at the Visking Corporation.

"When Visking was acquired by Union Carbide in 1957, Dr. Cooke analyzed himself. "I decided I was happiest when I was on a problem with a time limit where, come a date, I had to make a decision," he recalled. He volunteered for trouble shooting assignments in both technical and marketing areas.

"When the urban affairs post was offered, he felt he had no choice but to accept."

That same year, Cooke was awarded the 1970 William Procter Prize for Scientific Achievement presented annually to a scientist who has made an outstanding contribution to science research and has communicated the significance of this research to scientists in other disciplines.

It was during the early 1970s that Cooke also sustained a connection to his alma mater through his passion for Badger football. But it tested his problem-solving skills because there was little television coverage of the Wisconsin program in the New York metro area.

"Lloyd was a dedicated church-goer but he always made sure to get the family home by noon every Sunday so he could watch a 30-minute TV program of film highlights from the previous day's game," recounted Cooke's son, Bill, speaking for his mom, Vera, and sister Barbara.

"As we also know, the 1970s were the pre-Coach Barry Alvarez years and 'Wisconsin highlights' were sparse (only one winning season in that entire decade). But any glimpse of Badger red and white, whether in victory or defeat, would bring a cheer and a big smile from Lloyd."

Family and friends are now cheering his posthumous induction to the UW Athletic Hall of Fame, Class of 2021. Cooke was an integral contributor on the 1936 cross country team that won a share of the Big Ten title and was the first Black student-athlete to compete in the sport at Wisconsin.

Born in La Salle, Illinois (100 miles southwest of Chicago), he lettered in both track and field and cross country and was active in many different organizations. The family provided this collaborative glimpse into his life on the Madison campus that was rich with achievement in and out of the classroom.

"Lloyd was always clear that the University of Wisconsin played an unrivaled role in allowing him to achieve his potential as an athlete and professional. Throughout his life, he was very conscious of doors being closed to him, both metaphorically and physically, because of his racial background.

"The University of Wisconsin was a meritocracy which allowed him to flourish and for that he was eternally grateful. Lloyd was a self-admitted loner, hesitant to join groups. But he always proudly identified himself as a Badger."

• • • •

Vera Cooke (nee Schlegel) was a 1953 UW grad and biochemist at Visking Corp.

"We were co-workers," she said of her future husband, Lloyd, whom she married in 1957. "He was just a likeable person, an interesting and fun person to be with. I enjoyed his company and he enjoyed mine and I guess that's all it took."

For their honeymoon, they flew to Alaska. Lloyd piloted the single-engine plane.

"The weather got bad, and we had to make a forced landing on a dirt road," said Vera, recalling there was a scarcity of functioning mechanics at their disposal. "It was the Swedish Covenant Minister who fixed our plane and we visited McKinley National Park while it was being repaired."

When Cooke wasn't flying cross-country or cross-continent — another excursion took him to the Dairen National Park in Panama — he was hiking through the heart of Nepal's high Himalayan mountains.

"He was very adventuresome," Vera said.

Obviously, he was also conscientious about keeping track of the Badgers.

"Football wasn't that much part of my life," said Vera. "But it was definitely part of his."

In addition, she noted, "He liked to look back at his time at Wisconsin."

Cooke arrived on the UW campus in 1933. For historical context, it the worst year of the Great Depression. Unemployment hit an all-time low of 25 percent.

After his first two semesters in school, he was inducted into Phi Eta Sigma, an honorary scholastic society that put a spotlight on freshmen and their academic excellence.

As a sophomore, Cooke competed on the varsity track and field team and the cross country squad. He earned varsity letters during his junior and senior years.

One of the more memorable cross country snapshots came in 1935. In the opening meet of the season, the Badgers had six racers cross the finish line, simultaneously, arm-in-arm.

Among those making a statement were Chuck Fenske and Cooke, the bell-cows of the team. The following year, the Badgers went undefeated in five duals and a triangular meet.

Fenske, a junior captain, placed first or tied for first with a teammate in every competition. Cooke accounted for the second-most points with two firsts and three second-place finishes.

The year before, the Badgers lost only one Big Ten dual and that was to Illinois. In 1936, they avenged that defeat to the Illini by sweeping the top five places with Fenske and Cooke tying for first.

Over Cooke's final two seasons, Wisconsin posted a 9-2 record. Fenske, an outstanding miler, was inducted into the UW Athletic Hall of Fame in 1991. He's also in the Wisconsin (state) Hall of Fame.

In June of '36, Cooke and some of his teammates, including Fenske and Jack Kellner, participated in the national Olympic trials. Cooke placed fourth in the 3,000-meter steeplechase.

Asked about her husband's athletic endeavors, Vera said, "The fact that he could run fast and win accolades is what made him do it. He could win. And I guess one win stimulates others."

She admitted, too, that they never talked much about him breaking the color barrier to run cross country at Wisconsin. "It really wasn't much of our conversation," she said.

For more historical perspective, in 1934, Cooke's sophomore year, National Football League owners, in a secretive pact, banned black athletes from their sport, a ban that lasted until 1946.

That was the post-graduation world that he was entering after writing his senior thesis on "Quantitative Analytical and Concentration Methods for Rhenuins Ores."

Because jobs were tough to find, he went back to school and pursued his doctorate in organic chemistry from McGill University in Montreal, Quebec. He also ran track while getting his PhD in 1941.

Returning to the states after serving as a lecturer, he started his illustrious career as a manager and research chemist. His first book on environmental chemistry was adopted as a college text.

In 1969, he led a study for the American Chemical Society that resulted in the publication of "Cleaning our Environment: the Chemical Basis for Action" which was translated into 32 languages.

One of Cooke's crowning accomplishments, one that he was most proud of, according to his family, was his presidential appointment to the National Science Board (1970-1982).

During this period in his life, he used his vacation time to share the excitement of scientific research with elementary school students in the New York metro area.

After serving as Union Carbide's Director of Urban Affairs, he was the president of the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering and recruited minority students to the sciences.

In the '70s and '80s, he was still a serious runner and competed in the master's category. His capacity and gift for running matched his flair for problem-solving, all befitting of a Hall of Famer.